Map Courtesy - Encyclopedia Britannica

The existence of the Indo-European family of Languages is an undisputed fact well accepted in the academic world. It is the realization that a large number of very widely spoken and not so widely spoken languages, that spread across Eurasia in antiquity and now across the world, have a shared common origin. It is, in fact the largest family of languages in the world by population numbers and has been so for thousands of years. It is constituted by languages that are spoken by 95 % of the European population and 80 % of the population of the Indian subcontinent. In between the languages spoken on the Iranian plateau are also largely, around 79 % of them, part of the same family.

Those of the Indo-European (IE) languages that are spoken in Iran, Afghanistan, Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent are collectively subsumed under a massive sub-branch known academically as Indo-Iranian (IIr). The Indo-Iranian branch is truly massive even within the Indo-European family. As per Ethnologue, presently there are a total of 455 Indo-European (IE) languages spoken across the world out of which a whopping 312 (or about 68.5 % of all IE languages) are members of the single sub-branch of Indo-Iranian. The rest of all the branches in combination can only muster up a total of 143 languages apparently i.e. less than half of the total number of Indo-Iranian. This statistic is by itself so stark that it should spark an interest in the academic world to probe and understand it. This massive diversity of the Indo-Iranian languages is altogether spoken by about 1.6 billion people which make up about 50 % of all Indo-European speakers. How did this single branch of Indo-European, the easternmost one at present, outstrip the other IE languages, by so much both in terms of number of languages and number of speakers ?

While that remains a question that is not much probed or thought about, what has seized the attention of the academic world for more than 2 centuries now is the quest to find the place of origins of the earliest Indo-European speakers. There are two major theories that are the most popular today in the western academia for the origin and dispersal of Indo-European languages, namely the Pontic Caspian Steppe origin theory and Anatolian origin theory. Bizarrely enough, none of these theories are able to explain how the largest member of this family, Indo-Iranian, managed to spread into the Indian subcontinent (or Iran for that matter) from their respective proposed homelands of Steppe & Anatolia.

As James Mallory, one of the major proponents of the steppe origin theory states,

This is indeed the problem for both the Near Eastern and the Pontic-Caspian models and, following the logic of this analysis, the Bouckaert model appears to be in the same boat. All of these models apparently require the Indo-European languages (including their attendant agricultural vocabulary) to be superimposed/adopted by at least several major complex societies of Central Asia and the Indus...In any event, all three models require some form of major language shift despite there being no credible archaeological evidence to demonstrate, through elite dominance or any other mechanism, the type of language shift required to explain, for example, the arrival and dominance of the Indo- Aryans in India...all theories must still explain why relatively advanced agrarian societies in greater Iran and India abandoned their own languages for those of later Neolithic or Bronze Age Indo- Iranian intruders.

To summarise, whether it is the Anatolian origin theory or the steppe origin theory for Indo-European homeland, both of them require that the Indo-Iranian languages were intrusive into Iran, Central & South Asia (Indian subcontinent) that overwhelmed and transformed completely the linguistic landscape of relatively advanced agrarian societies of these vast densely populated regions, inspite of there being no archaeological evidence to support such an extraordinary transformation. The question that naturally arises is - why should one still insist on the veracity of such theories if they cannot explain the origin and spread of the Indo-Iranian branch which alone constitutes nearly 70 % of all spoken IE languages and 50 % of its speakers in existence today ?

The Age of Indo-Iranian in the Indian subcontinent

Thankfully, it now appears to be the case that, academic opinion in the west might just be coming on board in acknowledging and perhaps addressing this massive lacunae in the Indo-European origin story. In a major recent research paper published in the Science Journal, Heggarty et al (2023), using Bayesian phylogenetic methods applied to an extensive new dataset of core vocabulary across 161 Indo-European languages, report a new framework for the chronology and divergence sequence of Indo-European. As per their study, the root age of the ancestral language of all Indo-European languages, also termed the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language is about 8,120 years before present (ybp) and that by 7,000 ybp, it had already diverged into multiple different branches one of which was Indo-Iranian.

Source: Heggarty et al (2023)

According to Heggarty et al, the Indo-Iranian languages could have broken away as early as 7,000 ybp from the rest of the Indo-European (IE) languages and that they do not show particularly close affinity to any of the other IE languages, such as Balto-Slavic for example. The breakup of Indo-Iranian into its cinstituent branches, such as Indo-Aryan, Iranian & Nuristani, is dated by them to around 5,500 ybp which, incidentally, closely matches the conventional dating of the begining of the Early Harappan period while the breakup of Indic or Indo-Aryan into its daughter languages is dated by them to around 4,400 ybp which is just 2 centuries younger to the beginning of the Mature Harappan phase in 4,600 ybp.

Taking the latest ancient DNA data and conflating it with their own bayesian phylogenetics derived chronology & tree topology, Heggarty et al lend support to the South Caucasus/Northern Iran homeland theory of PIE. They argue that their dates suggest a very early breakoff of Indo-Iranian languages and an early spread of Indo-Iranian languages in the Indian subcontinent possibly in association with the CHG/Iran Neolithic related ancestry (a major source of subcontinental ancestry up to this day) .

Implicit in their analysis, is their disapproval of a late entry of Indo-Iranian into the subcontinent, as late as 3,500 ybp, possibly with the spread of 'steppe' ancestry, as suggested by the steppe theory of PIE origins. On the contrary, the results of dating methods used by Heggarty et al suggest that Indo-Iranian languages were likely present in the Indian subcontinent, from a very early period, from perhaps as early as 5,500 ybp if not earlier. This is a major setback for those who were certain that ancient DNA had somehow proven the spread of Indo-Iranian languages into the Indian subcontinent from the steppe.

The Improbability of a massive language turnover

While the Heggarty et al paper is the most high profile refutation of what is often referred to as the Aryan Migration Theory (AMT), previously also known as Aryan Invasion Theory (AIT), which proposes a migration of Indo-Aryans from the steppe into the Indian subcontinent around 1500 BCE, we may note that, there are several very weighty reasons, much apart from the results of Heggarty et al study, to reject the AMT and look at the Indian subcontinent itself as the most likely place of the breakup and diversification of not only the Indo-Aryan but the Indo-Iranian languages as a whole which make up more than 2/3rd of all IE languages spoken across the world today. Many of these reasons have been highlighted in recent years by prominent western scholars in prestigious publications.

As Heggarty (2013) notes in an earlier article, in The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration, as a critic of the likelihood of the steppe nomadism bringing in the Indo-Iranian languages to the subcontinent, Mounted ‘Aryans’, bursting out of the Steppes to invade, conquer, and thereby impose their languages upon India, Europe, and all points between, certainly make for a stirring migrationist picture long popular among Indo-European linguists, yet it faces strong objections on all levels. The image seems powerful in the light of much later histories, at least, of Turkic-, Mongolic- and Uralic-speaking peoples or ‘confederations’, such as the Huns or Xiōngnú. Their names appear as sources of dread to the populations of India, China and Europe, over which Steppe invaders at times succeeded in imposing themselves as a dominant elite. Firstly, however, these precedents date only to historical times; it is an anachronism to assume any necessary analogy with lifeways on the Pontic-Caspian Steppe millennia earlier, so long before the key inventions of saddle or stirrup, and at a time for which it remains disputed whether horses were being ridden at all...

Secondly, almost every known ‘precedent’ is in fact a counter-example to the Steppe hypothesis, linguistically. Dominant elites the invaders may have become, but whenever they subdued already densely settled agricultural regions the one battle they most consistently lost was the linguistic one. India and Europe speak no native Turkic or Mongolic tongues today, but continue their own Indo-European. It was precisely the incoming elites who were serial learners of the native languages of the populations they conquered.

As the highlighted text points out, there is no historical precedent in the Indian subcontinent of an invader whether from the steppe or elsewhere, who has managed to impose their language on the people native to the region. It is therefore quite extraordinary to claim, with no archaeological evidence to back it up, that some handful of migrants from the steppe in around 1500 BCE were able to absolutely transform the linguistic landscape of much of the densely populated Indian subcontinent, except in the south. Such an extraordinary claim is now even more suspect with the recent phylogenetic paper of Heggarty & team published in Science which push the date of Indo-Iranian and Indo-Aryan unity and therefore their entry in the Indian subcontinent, much before the proposed dates of steppe migration into the region.

However, the most rigorous academic argument in the west in favour of the origin of Indo-Iranian languages within the Indian subcontinent itself, has been made by Renfrew & Heggarty (2013), published in the 3 volume Cambridge World Prehistory. They make no bones about the lack of consensus on the origin of Indo-Iranian languages in the region,

As for the origins of the Indic languages of so much of South Asia, there is even less consensus. Indeed it is here that both main hypotheses for the spread of the Indo-European family as a whole – whether with agriculture out of central and eastern Anatolia, or with horse-based pastoralism out of the Pontic-Caspian Steppe – face perhaps their most significant challenges.

From the foregoing discussion, we have already noted two important points that go against the theory of an intrusion of the Indo-Iranian languages in the Indian subcontinent from somewhere outside the region especially as late as 1500 BCE :-

1. Lack of any archaeological evidence to suggest any foreign material cultural intrusion in the subcontinent that could have acted as a vector for the inflow of Indo-Iranian languages into the region. This is especially jarring since the Indo-Iranian languages overwhelmingly dominate the vast region stretching from Afghanistan in the west to Bangladesh in the east with very little space for any non Indo-Iranian language in its midst. In contrast, the steppe intrusion that is supposed to have spread Indo-European languages into Europe in the 3rd millennium BCE is archaeologically very well attested and it even created its own new steppe based culture known as the Corded Ware culture.

2. No historical precedent in the Indian subcontinent that shows any migrating or invading nomadic pastoralist group whether from the steppe or elsewhere being able to change the linguistic landscape even in a small area of this vast densely populated region.Rather, all those invasive forces assimilated into the existing linguistic landscape. Even the Islamic rulers, who were mostly of foreign origin and who used the foreign Persian language for administrative purposes in the region, failed to implant any foreign language among the people of the subcontinent, including among those who converted to Islam.

Heggarty & Renfrew (2013), advocate that while they do not support the idea of Indian origin of the whole family of Indo-European languages, they are very much in favour of early migration of the Proto-Indo-Iranian language into the subcontinent following which it could have gone on to expand and diversify into Indo-Aryan (Indic), Iranian & Nuristani branches within the subcontinent itself. They make a very compelling case in favour of it which we can break up into 3 points. These we can add to the 2 points we have already summarised.

3. The Indo-Iranian diversity in the Indian subcontinent vis-a-vis the steppe

Heggarty & Renfrew (2013), observe that unlike the steppe from where the Indo-Iranian languages are purported to have originated, the diversity and antiquity of these languages in the subcontinent is much greater.

The earliest known distributions of Indo-Iranic languages are concentrated on the southern route. Some representatives of Indo-Iranic do eventually appear on the Steppes, notably Scythian, Bactrian and Sogdian, but are not attested until the 1st millennium BCE. Even on a short chronology, this is a thousand years at the very least after Indo-Iranic had split up, and many centuries after its Indic branch too had already begun diverging into India.

Regarding the earlest attested presence of Indo-Iranian languages on the steppe, they state -

...none of these Steppe representatives is Indic; they are only Iranic, indeed all specifically Eastern Iranic. That is, the only presence here is of languages specific to a lineage already discrete even from other Iranic languages, let alone Indic. Their identity postdates considerably the Indic-Iranic split; so too, then, most plausibly and economically, did these languages’ arrival here.

Heggarty & Renfrew (2013) point out that even Eastern Iranic's presence on the steppe is likely due to a migration into it from elsewhere probably from the south,

It is necessarily a late intruder, and from far to the east and south – where its immediate origins lay, together with its ancestral forms and nearest relatives. Avestan, as very early Eastern Iranic, is the one language we know of that is closest to the common ancestor of Eastern Iranic; and wherever precisely Avestan hailed from, it was patently not the Pontic-Caspian Steppe. On the Steppes, Eastern Iranic is found only relatively late, and alone. In the northwestern corner of South Asia, however, it coexists alongside all of its closest relatives. On Occam’s logic of parsimony, this is most plausibly the result of a single northward movement, at a stage after its specific lineage had had time to crystallise out of Proto-Indo-Iranic, and through Proto-Iranic. This militates against a Steppe origin for general Indo-Iranic.

By contrast, the diversity of Indo-Iranian in the subcontinent is unquestionable and self-evident. Making a case for the agricultural hypothesis (Near Eastern origin of IE) they assert,

Conspicuous by their absence from the Steppe are all the other branches of Indo-Iranic, resulting from its earliest divergent splits: i.e. western as well as eastern sub-branches of Iranic; Nuristani; and Indic itself, including its own earliest divergent branch of Dardic. All are first attested along the southern route; several abundantly so, and long before Eastern Iranic on the Steppes. And the only region where representatives of all of them are found – and indeed all in close proximity to each other – is in the highland redoubts around the Upper Indus, the clear focus of diversity within Indo-Iranic. The homeland out of which Proto-Indo-Iranic began to spread and diverge would by default be assumed to be somewhere near these remote mountains where this diversity survives. Languages from all of Indo-Iranic’s first branches are spoken within a few hundred kilometres or so of Harappa, in the northern arc of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, the gateway from Indus to Ganges. This is the same general region where the agriculture hypothesis would predict that these branches would have split from each other, as agriculture finally spread towards the Ganges after its long pause on the Indus.

Heggarty & Renfrew thus make it clear how the Indo-Iranian linguistic diversity within the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, where all of its earliest branches exist, is far greater than its diversity elsewhere, whether on the steppe or in West Asia. This is the 3rd major argument that militates against the Indo-Iranian languages originating somewhere else outside the subcontinent aside from the lack of any historic precedent for a language turnover in the region inspite of many invasions and also lack of any archaeological evidence for any Indo-Iranian intrusion from outside in the given prehistoric period.

4. The antiquity and temporal depth of the Indo-Iranian languages in the subcontinent

The all encompassing diversity of Indo-Iranian languages in the Indian subcontinent also makes it difficult to ignore the resulting deep antiquity of these languages in the region. Rigvedic Sanskrit is itself dated, even by most western scholars, to not later than the mid 2nd millennium BCE i.e. around 1500 BCE or thereabouts. However, Vedic Sanskrit is not even the ancestor of the Indo-Aryan or Indic branch of Indo-Aryan but is only a cousin of the Prakrit languages from which most modern Indo-Aryan languages descend. Vedic itself has even undergone some change from the stage of the purported proto-Indic ancestor. This pushes the antiquity of ancestral Indo-Aryan or proto-Indic language several centuries anterior already to the Vedic Sanskrit date of approximately 1500 BCE (itself a very conservative date for Vedic).

Heggarty & Renfrew explain this as under -

The diversity of today’s Indic languages goes back to contexts and processes much earlier in prehistory. It does not even trace back directly to Vedic, but effectively to what are known as the Prākrits (loosely, “vernaculars”). As Lazzeroni (1998: 102) puts it, the Prākrits “do not derive from Sanskrit in the same way that the Romance languages derive from Latin”; and specifically, they “do not go back directly to the dialect which formed the basis of Vedic” either. The Prākrits and Sanskrit were close relatives, to be sure, but even by the time of Vedic they represented various separate, parallel language lineages. Amongst them, Vedic itself can already be distinguished as a “far-western dialect”.

The fact that needs to be noted here is this - whatever may be the antiquity of the Vedic Sanskrit language, whether 1500 BCE or earlier, even during that early period of its existence in the 2nd millennium BCE, the Indic or Indo-Aryan languages had already diversified into various separate lineages. This is not a controversial but a well-accepted fact even among the western linguists. This fact often forces many western linguists, who want to keep on holding to the migration argument, to propose for atleast two Indo-Aryan migrations into the Indian subcontinent with the Vedic Sanskrit migration being considered later to the other Indo-Aryan migration.

That other Indic lineages are identifiable, and cannot be traced back to Vedic itself, entails some non-negligible timespan, before the Ṛgveda, over which they had all already been diverging from each other out of their true common ancestor language...Other Indic languages with early written records confirm this, not least the Pāli of many early Buddhist scriptures, and the liturgical language of the Theravada branch (Masica 1991: 51–3). Pāli too “is not a direct continuation of Ṛgvedic Sanskrit; rather, it descends from [. . . dialects] different from Ṛgvedic” and indeed “in several points more archaic than Ṛgvedic Sanskrit” (Oberlies & Pischel 2001: 6). The last point is especially revealing: Ṛgvedic had changed with respect to Proto-Indic, further confirmation of the time-gap between them.

It might be reasonably argued therefore that the period from a proto-Indic ancestor to the Vedic Sanskrit and its sister dialects stretched into several centuries at the very least. Nevertheless, the Indian subcontinent is not just the likely place of origin of Indo-Aryan or Indic but that of the Indo-Iranian family as well, as asserted by Heggarty & Renfrew themselves. While Vedic Sanskrit and Avestan are often taken to be very early examples of Proto-Indo-Aryan & Proto-Iranian respectively that were very close to each other, Heggarty & Renfrew assert, and we can see that in the latest phylogenetic paper (Heggarty et al 2023) we discussed at the start, that the apparent closeness of Vedic Sanskrit & Avestan can be very deceptive, especially in figuring out the time from their common ancestor.

Talking down the differences between Vedic and Avestan in fact sits rather ill alongside other forms of linguistic data. In particular, it is all too often overlooked that we have not one but two stages of language divergence to account for here. Firstly, Vedic Sanskrit is not the direct ancestor of all Indic, but is itself already identifiably changed since the Proto-Indic stage; more so, indeed, than some of its sister dialects (see p. 541). Vedic necessarily postdates Proto-Indic itself. Avestan, meanwhile, is not Indic at all, but Iranic. So to go back to its common ancestor with Vedic, we must take a further step back in the genealogy, and in time, to Proto-Indo-Iranic.

...Realistically, the plausible brackets of dates – both from the Ṛgveda back to the earlier Proto-Indic split, and then to the still earlier Proto-Indo-Iranic divide – are wider than many would have it, particularly in the direction of perhaps being rather earlier, by the order of several centuries. Even on the majority view of c. 3500 BP as the date of the Ṛgveda, the chronological leeway we must allow, to trace back to the expansions of Proto-Indic and then Proto-Indo-Iranic, can take us back squarely into the late Indus Valley civilisation...

...given the wide bounds of uncertainty that attend our chronological estimates, the gap between Proto-Indo-Iranic and Proto-Indic may be of the order of a few centuries, or up to a millennium or so.

The sum total of the argument is that the Proto-Indo-Iranian ancestral language, must have begun its earliest diversification in the Indian subcontinent, several centuries if not upto a millennium or more from the Vedic Sanskrit period of around 1500 BCE. Even such a conservative estimate, lands the diversification of Indo-Iranian languages in the Indian subcontinent squarely during the time of expansion of the Harappan civilization and agricultural expansion in the Gangetic plains. Even the geography of Indo-Iranian diversification, specifically in the northwest of the subcontinent, matches very well with the geography of the Harappans.

We are thus increasingly led to the inference that the Indo-Iranian languages must have already begun diversifying within the same geography and during the same period as the expansion of the earliest urban civilization of the Indian subcontinent i.e. the Harappan or Sindhu-Saraswati civilization.

5. The Cultural Process responsible for Indo-Iranian Expansion

Indo-Iranian and Indo-Aryan languages have the greatest expansion of any language family within the Indian subcontinent. This language expansion was also a prehistoric one and definitely did not happen with any historically known invasions or migrations from the northwest. The prehistoric expansion of Indo-Iranian languages within the subcontinent must have taken place by necessity through one of the greatest if not the greatest cultural and demographic processes in the history of the region that would have encompassed a large part of the subcontinent.

As Heggarty & Renfrew (2013) point out -

It is well to recall here a first principle in language prehistory (see Chapter 1.3, pp. 20–1) that patterns in the distribution and diversification of languages into families are only the outcomes of real-world processes acting upon the populations that speak them. With that cause-and-effect relationship goes also a principle of commensurate scale: logically, the greatest linguistic impacts would result from the most powerful processes shaping prehistory, not least in demography.

In prehistory, we rely on archaeology to identify that power socio-cultural and demographic processes. As far as the proposed theory of Indo-Aryan migration into the subcontinent goes, from the steppe or elsewhere, there is ZERO archaeological evidence for it. On the contrary, 1500 BCE is around the time, the Harappan civilization was declining and unravelling and therefore a period of unlikely culturo-social or linguistic expansion.

Heggarty & Renfrew point to the most dominant or powerful phenomenon that shaped the prehistory of the subcontinent,

In the Subcontinent, first among those defining processes were the rise of the Indus Valley civilisation, and the spread of farming eastwards into the Ganges Basin. It would not seem forced, then, but a starting assumption, that the language lineages dominant here from approximately those time-depths – namely, Iranic and Indic – might stem from those same expansive processes.

Elsewhere, explaining how they fit the expansion of Indo-Iranian language within the agricultural hypothesis, Heggarty & Renfrew, give a more detailed overview of the same process,

For the agriculture hypothesis, the main candidate process is clear, within the general subsistence/demography type of language expansion (see Chapter 1.3, pp. 38–40). The net gains in population growth and density that come with farming would have seen the population of the Indus Valley rise significantly, permitting – if not positively encouraging – the eventual expansion into the Ganges Basin, whose own rich agricultural lands would only have reinforced the process. A demographic “wave of advance” (see Renfrew 1987: ch. 6) eastwards along the Ganges Valley, and southwards from it, would also predict both of the clines we observe linguistically: the dialect continuum across Indic; and, as the proportion of incoming to indigenous genes declined away from the northwestern entry point, increasing language shift and stronger substrate effects.

Summarising, we can note 5 very solid points that inescapably lead us to consider the expansion, break-up & diversification, if not the origin, of the Proto-Indo-Iranian language into its descendent languages, to have happened within the Indian subcontinent itself :-

1. Lack of archaeological evidence in support of Indo-Iranian intrusion into the subcontinent.

2. Lack of historical precedent for any invasive force being able to force the change of language in the subcontinent.

3. The greatest diversity, by far, of the Indo-Iranian languages, within the northwest of the Indian subcontinent itself where all of its branches are present, which is far greater than Indo-Iranian linguistic diversity elsewhere in Eurasia including on the steppe.

4. The great time-depth of Indo-Iranian language expansion in the northwest of the subcontinent, going as far back as the period of Harappan expansion, with both processes also complementing and matching each other geographically.

5. The only great socio-cultural and demographic process in the prehistory of the Indian subcontinent, that too, within the north & northwest of the Indian subcontinent, that could have acted as a vector for the expansion of the Indo-Iranian languages in the region, was the expansion of the Harappan civilization and the farming expansion in the Gangetic plains.

Points 3 to 5, make a very strong case for the expansion & diversification of Indo-Iranian languages in the Indian subcontinent with the expansion of the Harappan civilization itself from around the 3rd millennium BCE itself or earlier. Taking that in combination with points 1 & 2, it becomes extremely unlikely that an Indo-Aryan migration, that too, in the post-Harappan period, could have instead led to the intrusion of Indo-Aryan or Indo-Iranian languages in the Indian subcontinent.

The latest phylogenetic paper of Heggarty et al (2023), effectively puts a further seal of approval to this theory for the explanation of the most plausible socio-cultural demographic event of the subcontinent i.e. the emergence of the Harappan civilization. We may thus assert that even as per the western academic consensus, there is now increasing acceptance that the largest branch of Indo-European, the Indo-Iranian, which constitutes nearly 70 % of all IE languages in existence today, must have expanded and diversified for the first time within the northwest of the Indian subcontinent itself.

The True Complexity and Diversity of the Indo-Iranian languages in the Subcontinent

While Heggarty & Renfrew (2013) make a logically devastating case against a relatively late 2nd millennium BCE intrusion of Indo-Iranian languages into the region and in favour of Indo-Iranian expansion within the Indian subcontinent itself from the Harappan period already if not earlier, Claus Peter Zoller, has gone on to document a rich set of data from the Indo-Iranian languages of the same region and shown just how complex and diverse the Indo-Iranian languages of the subcontinent really are which lends further credence to the arguments of Heggarty & Renfrew (2013) of Indo-Iranian expansion in the region from the proto-stage itself.

1. Inner Language Indo-Aryan (IA) - Vedic Sanskrit and its descendents, Classical Sanskrit, Classical Prakrit Languages, Hindi etc.

2. Outer Language Indo-Aryan (IA) - Nuristani, Dardic, Western Pahari, Assamese, Chittagongian, Rohingya etc.

In this formulation of Outer and Inner IA, Zoller is not the first but follows in the footsteps of Hoernle, Grierson and to some extent Southworth in recent times. But Zoller's work brings together a lot more new data to the table and his formulation is much more incisive & specific. As per Zoller, however, there are no fully Outer or fully Inner Indo-Aryan languages but rather Indo-Aryan languages who either have more Outer Language features or more Inner Language features.

According to Zoller, Nuristani was not a separate 3rd branch of Indo-Iranian but rather one of the sub-branches of the Outer Language (OL) Indo-Aryan.

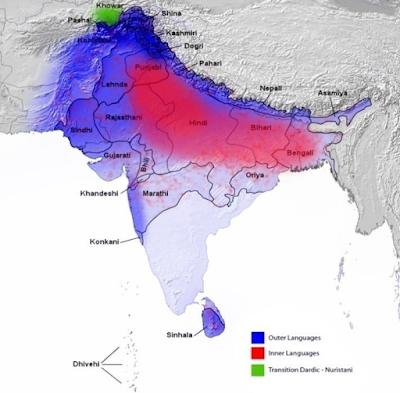

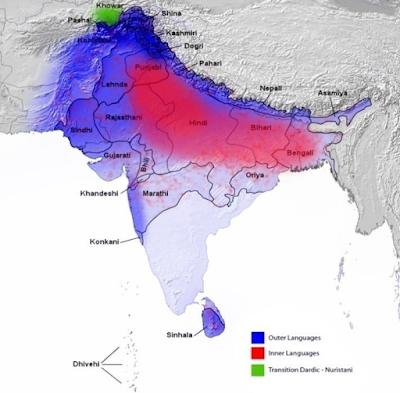

The geographical expansion of the Outer and Inner Indo-Aryan languages in the Indian subcontinent can be understood as per the following map of Zoller.

The area largely marked in red represents the region where the Inner Language features dominate while the blue and green represent the areas where the Outer Language features are much more abundant. This is a general scheme and not absolute as even within the Inner Language area there are languages which have a great number of Outer Language features and similarly within the Outer Language area we have languages with mostly Inner Language features. For example, while Hindi is an Inner Language, geographically proximate languages such as Brajbhasha & Awadhi, which overlap in geographical distribution with Hindi in parts of North India which maybe considered as Inner Language area, have a lot of Outer language features.

As per Zoller's model, the Outer Languages must have been brought to the subcontinent by the 1st Indo-Aryan migrants who intruded into the region while the Inner Languages were brought by a later group of Indo-Aryan migrants who could have come later to the first wave by as much as 500 years. It is these later second wave Indo-Aryans apparently who composed the Vedas. Since Rigveda itself dates to around mid-2nd millennium BCE, even as per Zoller's model, the speakers of Outer Languages, who apparently migrated earlier to the Vedic Indo-Aryans by as much as 500 years, must have migrated to the Indian subcontinent already during the later phase of the Harappan civilization.

Outer Indo-Aryan, Inner Indo-Aryan & Iranian

While Zoller frames his discoveries and theories within the framework of the steppe origin Indo-Aryan migration theory, we shall now look into those aspects of Zoller's findings which, inadvertently for him, end up making a very strong case for the earliest Indo-Iranian expansion & break-up within the Indian subcontinent itself.

Zoller, while arguing for an Outer Indo-Aryan migration into the subcontinent preceding the Inner Indo-Aryan migration by several centuries, rather intriguingly, also proposes that this Outer IA must have come into the Indian subcontinent together with the Iranian languages.

As he states,

Johanna Nichols’ axiom (1998: 252), “[t]he relative chronology for entries to India is therefore Indic, then Nuristani, then Iranian” is no longer tenable and ought to be replaced by: The relative chronology for entries to northwestern South Asia is Outer Languages Indic (including Nuristani) roughly simultaneously with Iranian, then Inner Languages Indic.

Why does Zoller make such an argument ? As per Zoller, the Outer Languages, together with Iranian, preserve an archaism inherited from the Proto-Indo-European & Proto-Indo-Iranian period, where the Inner Indo-Aryan, Vedic and its descendents, show innovation. For example, Nuristani languages are considered particularly archaic mainly because of their preservation of the PIE distinction between palato-velar and labiovelar stops in the form of two phonologically contrasting affricate series. This distinction is also preserved in Iranian at an initial stage while it is not present in Vedic Sanskrit and this is considered a major distinguishing factor between Iranian & Indo-Aryan. However, according to Zoller not only Nuristani & Iranian but even many Dardic, West Pahari and many other Outer Indo-Aryan languages managed to preserve the two contrasting affricate series.

Apparently, the PIE palato-velars k̂, ĝ & ĝh changed into Proto-Indo-Iranian ć, j́ & j́h. Vedic or Inner Indo-Aryan "preserved the palatal stage of Proto-Indo-Iranian: PIIr. *j́ was preserved unchanged, *ć lost its closure and turned into OIA ś, in * j́h the aspiration was preserved."

In Iranian and Nuristani, these palatal affricates changed into dental affricates *ts (from ć) and *dz (from j́ & j́h) respectively while losing aspiration in j́h. Nuristani preserved this dental affricate stage while in Avestan *ts & *dz was deaffricated into s & z and in Old Persian into θ & d.

As per Zoller,

Certain non-Vedic Proto-and (pre-)Old Indo-Aryan lects underwent a similar process as Iranian and Nuristani because also they arrived in South Asia long before the Vedic speakers. However, it is likely that dentalization (and deaffrication) spread over centuries through the lects of this early immigration...already around 2,000 years ago one finds dental affricates (plus a unique z phoneme) in an Indo-Aryan language.

Zoller notes that the dentalized affricates are found in many non-Vedic Indo-Aryan languages, ancient & modern, with many of these Indo-Aryan languages also undergoing deaffrication similar to Iranian.

Having understood the supposed transformation of Proto-Indo-European palato-velars in Indo-Iranian, Zoller informs us that PIE velars and labio-velars were at a later stage also palatalized (i.e. later than PIE *k̂) in Proto-Indo-Iranian *č under certain phonetic conditions.

Zoller then points out the crucial distinction between Vedic & Iranian/Nuristani languages,

However, different from the fate of PIIr. *ć, PIIr. *č was kept in Old Indo-Aryan and in Old Iranian in a very similar fashion...whereas Iranian and Nuristani preserved to a certain extend the opposition between palato-velars and (labio-)velars as one between palatal and dental affricate (still preserved in Nuristani but debuccalized or changed into fricative in Iranian long ago), the same distinction was preserved in OIA as one between palatal sibilant ś and palatal affricate c.

This is infact the crucial distinction that characterises Iranian and Vedic. While in proto-Iranian, the distinction between PIE palato-velars and labiovelars was preserved as a distinction between dentalized (*ts, *dz) and palatalized affricates (*č), in Vedic, the distinction was reduced into 1 palatal sibilant (*ś) and a single palatal affricate (*ć). Thus Vedic only had one affricate order compared to Proto-Iranian two.

Zoller points out that in contrast to Vedic or Inner Indo-Aryan, the Nuristani, Dardic, West Pahari & other Outer Indo-Aryan languages also preserved this Proto-Iranian distinction between palatal & dental affricates. Even when it comes to the Indo-Aryan deep inside the subcontinent Zoller notes,

While classical Inner Languages such as Sanskrit, Pali and Hindi show no traces of dentalizations, there is a whole range of New Indo-Aryan languages that share the phonological characteristic of having only one set of affricates with the classical Inner Languages, but whose only palatal affricate series was dentalized. Masica quotes (1991: 94) “Nepali, Eastern and Northern dialects of Bengali (Dacca, Maimansing, Rajshahi), the Lamani and northwestern Marwari dialects of Rajasthani, the Kagani dialect of ‘Northern Lahnda’, Kumauni . . . ”...in Rajasthan (southern Śaurasen¯ı area) and in Gujarat both c and ch are pronounced as s, and in North Gujarat j and jh are pronounced as z (p. 393f.). “This s and this z are often pronounced as ts and dz respectively” (p. 394). This has certainly a parallel in Chittagongian initial s- as for instance saır ‘four’ was formerly pronounced as tsaır (cf. Bng. ċār)...the evidence from much earlier Greek writers and the indirect evidence from Chittagongian and some other modern languages leaves little doubt that previously Indo-Aryan languages with two affricate orders must have existed from the Indus Valley to the Bay of Bengal.

The presence of a dental affricate as well as two affricate orders in the past in such Indo-Aryan languages, stretching from Indus Valley to Bay of Bengal, which is unlike Vedic & its descendent languages but present in Nuristani & Iranian and is a fundamental feature of distinction between Vedic & Iranian for linguists, is a clear indication of the fact that many Indo-Aryan languages in the initial Indo-Iranian phase had more in common with Iranian than Vedic. These Indo-Aryan languages are classed by Zoller as Outer Indo-Aryan.

According to Zoller (pg 85),

The split into Iranian and Indo-Aryan took place through two very different linguistic-historical processes. While on the Iranian side – including some non Vedic Indo-Aryan dialects – the phonological difference between palato-alveolar and palatal affricates continued to be retained in form of an opposition between alveolar and postalveolar affricates (see Klein et al. [2017: 482]) – that is, two different places of oral stricture were retained – whereas in Vedic Indo-Aryan the palato-alveolar and the palatal positions merged into one common palatal position.

Thus, at the very fundamental stage of Indo-Iranian break-up and diversification, Outer Indo-Aryan preserved the more archaic phase in common with Iranian of two affricate orders (palatal & dental) while Inner Indo-Aryan underwent an innovation (only 1 palatal affricate with other affricate turned into a palatal sibilant). Later on, Iranian underwent innovation of its own whereby the dentalized affricates deaffricated and turned into sibilants s & z while Nuristani and many Old Indo-Aryan languages preserved the dentalized affricates *ts & *dz.

Due to this fundamental similarity in affricate series between Outer Indo-Aryan and Iranian, to the exclusion of Inner Indo-Aryan, which is evident at the very stage where Indo-Aryan & Iranian are considered to have broken up, Zoller is forced to argue, under a migration paradigm, that Old Indo-Aryan and Iranian must have migrated into the Indian subcontinent together while Inner Indo-Aryan must have come centuries later into the region.

In addition to this there are also a few other shared features between Outer Indo-Aryan & Iranian that he highlights such as loss or gain of aspiration - observed in Nuristani, Dardic, Western Pahari and neighbouring Iranian languages but not in Vedic & Inner IA - & the process of assimilation of clusters observed in Outer Indo-Aryan and Iranian but which has given way to simplification in Inner IA.

What is extraordinary is the implication that the earliest wave of Indo-Aryan expansion across the subcontinent of a language which was at the basic level more like Iranian than Vedic and which shared Proto-Iranian features rather than Proto-Vedic.

Zoller (pg. 466), even suggests that the earliest migrants (Old Indo-Aryan & Iranian) into the subcontinent could be called as "(late) Proto-Indo-Iranian" while the latter IA migrants, speakers of Vedic Sanskrit, could be called as "Old Indo-Iranian". Implicit in such a formulation is the acknowledgement that the earliest migration into the Indian subcontinent dates to a period before the break-up of Indo-Iranian into Indo-Aryan & Iranian. Infact Zoller even goes so far as to argue that, while he does not consider Nuristani unique enough to constitute its own 3rd branch of Indo-Iranian and brackets it under Outer Indo-Aryan, it is certainly more plausible to consider a 3 way break-up of Indo-Iranian into Outer Indo-Aryan, Inner Indo-Aryan & Iranian.

As an alternative worth considering, one could regard the Outer Languages – which never underwent significant standardizations – as the third branch of Indo-Iranian instead of Nuristani. They form a link between Iranian and Indo-Aryan: they are closer to Indo-Aryan than to Iranian but they share some features with Iranian not found in Indo-Aryan.

However, Zoller finds that such a simple 3 way classification of Indo-Iranian languages while convenient, does not adequately explain the complexity of it all. Instead of the standard 3 way model of Indo-Iranian classification (above), Zoller attempts to explain his classification with the following diagram (below) where the Outer Indo-Aryan does not represent 1 single branch of Indo-Iranian but several different smaller branches (OL1, OL2, etc) which form a link between Iranian and Inner Indo-Aryan through what he calls a linkage of lects. In other words, the Outer Indo-Aryan, which had more in common with Iranian than with Vedic during the early Indo-Iranian period, cannot even be termed a single branch but several different branches with varying levels of overlaps between Iranian & Vedic (Inner IA).

Zoller explains his position thus,

Instead of the traditional Indo-Iranian dichotomy(Iranian – Indo-Aryan) or tripartition (with Nuristani somewhere in between), the concept of a linkage of lects is introduced, which is closer to the linguistic realities...the mutual overlaps (between Iranian & Indo-Aryan languages) can be explained by the fact that among the lects of the Indo-Iranian linkage there were a few Iranian and Indo-Aryan lects that have not completely separated from each other...not all dialects completely separated from each other in the post-proto-Indo-Iranian phase. This concerns several archaisms and innovations usually considered as characteristic for either Iranian or Indo-Aryan.

Zoller's proposition seems to be that if one were to trifurcate the Indo-Iranian family, then it is better to divide it into 1. Outer Indo-Aryan. 2. Inner Indo-Aryan. 3. Iranian. However, the reality on the ground is even more complex and Outer IA might be divided into many multiple Outer Language groups with many overlapping features between them.

Zoller is ready to make such a complex proposition because apparently the Indo-Aryan (inclduing Nuristani) & Iranian languages in the NW of the subcontinent appear to share with each other many archaic overlapping features, which are usually considered either to be strictly Indo-Aryan or Iranian, and that this harkens back to the time when the Indo-Iranian languages had not quite broken away from each other. In other words, the Indo-Iranian languages in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent have still preserved many archaic features harking back to the very early stages of Indo-Iranian unity when early Indo-Iranian languages were in close contact with each other as they still are in that northwestern region. According to Zoller this is a reflection of the fact that during prehistory when Indo-Iranian unity was broken, several of these early Indo-Iranian dialects emerged besides Proto-Vedic & Proto-Iranian, which are the ancestors of the modern Outer Indo-Aryan languages. These early dialects often showed overlapping Iranian and Vedic features and there was no strict separation between Iranian features or Vedic features between them. The modern linguistic situation in that region is a reflection and continuation of such a complex prehistory.

Again as Zoller puts it (pg 38),

...the concept of a linkage of lects (Zoller [2016: 104ff.]) describing the developments of significantly more than three ‘branches’ out of Proto-Indo- Iranian is of better explanatory adequacy. Since monophonemization of ts > ts – versus Proto-Iranian ts > s and versus Old to Middle Indo-Aryan ts > (c)ch – is found from eastern Afghanistan to the Valley of the Yamuna (for examples see right below.), it has obviously manifested itself in a linkage of lects reflecting an ancient language geography where the ancestors of Eastern Iranian, Nuristani and West Pahāṛī were in direct contact – as they still are.

A Karvelian Substrate in North India ?

Zoller's most novel theory is however that there was a proto-Kartvelian substrate in the north-northwest of the Indian subcontinent, of which Burushaski is but a remnant, and which affected and fundamentally changed the phonology of both Outer Indo-Aryan & Proto-Iranian. According to Zoller, it is influence of Karvelain phonology that led to the distinction between Outer & Inner Indo-Aryan.

Linguistically, the Kartvelian substrate is of great historical importance, since it was the main reason for the separation of Outer and Inner Languages in Proto-Indo-Aryan times. Out of a certain number of Proto-Indo-Aryan dialects, some came under the influence of the Kartvelian phonological system (see next section). As a result, not only the phonological system of Burushaski but also the phonological systems of Dard and Nuristani languages, of eastern Iranian languages and of northwestern Tibetan languages have great similarities ultimately with the phonological system of Proto- Kartvelian. While the phonological systems of the Inner Languages (e.g. Classical Sanskrit, Pali, Hindi) simply evolved directly from the Proto-Indo-Iranian system, the Dard, Nuristani, and Eastern Iranian languages did not...based on the blueprint of the proto-Kartvelian phonological system, the Outer Languages, in contrast to the Inner Languages (but together with the neighboring Iranian and Tibetan languages), developed complex phonological subsystems in stops, affricates and sibilants. As a result of this divergence, different linguistic processes developed for the Outer and Inner Languages as early as the Indo-Iranian period (because some processes relevant for Outer Languages affected also various Iranian languages)...(pg 11)

Zoller is also quite clear that Proto-Kartvelain phonology has also fundamentally affected Proto-Iranian as well (pg 137),

We can see that, at least in terms of terminology, there is a striking resemblance between the Proto-Kartvelian and the Proto-Iranian (or ‘Khowar type’) subsystems, where both posses a post-alveolar series of affricates. Proto-Kartvelian is somewhat more complex compared to the single Proto-Iranian alveolar series with two Proto- Kartvelian series of pre-alveolar and mid-alveolar series. However, for the modern Kartvel languages, Heinz Fähnrich only differentiates between pre-alveolar and postalveolar affricates and spirants (see Fähnrich 2002)). This intra-systemically unmotivated further advancement of the position of stricture of the two affricate-sibilant series in Proto-Iranian can only be explained by influence of the Kartvelian affricate system. This system is widespread until today not only in modern Iranian languages but also in other language families and groups in northwestern South Asia.

We may thus surmise from Zoller's arguments that both the Outer Indo-Aryan and Proto-Iranian phonological systems were fundamentally shaped by the Kartvelian phonological system in NW Indian subcontinent. At the same time, the period during which Outer IA and Iranian are supposed to have entered the subcontinent is as early as the late Proto-Indo-Iranian period. So in theory, a breakaway branch of Proto-Indo-Iranian was fundamentally shaped by contact with Kartvelian phonology and this branch later on broke up into branches of Outer Indo-Aryan and Proto-Iranian. On the other hand, that branch of Proto-Indo-Iranian which was phonologically unaffected by Kartvelain, morphed into Inner Indo-Aryan.

Summary of Zoller's findings of fundamental importance

Zoller's research has 4 fundamental observations that further solidify the argument of Proto-Indo-Iranian expansion and break-up within the Indian subcontinent

1. Zoller's language map appears very weird if we were to look at it from the perspective of Indo-Aryan migrations from the steppe where apparently Outer Indo-Aryan was followed into the subcontinent by Inner Indo-Aryan from the northwestern corridor. Had that scenario been true, one should expect Inner Indo-Aryan displacing the Outer Indo-Aryan in the northwest of the subcontinent as they would have moved in firstly from that very direction thus pushing the Outer Indo-Aryan speakers in the northwest to further east inland. Instead, what we see is that Inner Indo-Aryan has displaced Outer Indo-Aryan from a central region while being surrounded on all sides by Outer IA with Outer IA being most concentrated in the very northwest region of the subcontinent where they should ideally have been pushed out from. This is counter-intuitive to what one would expect from two waves of Indo-Aryan migrations into the subcontinent from the NW corridor. On the other hand, the central region in Zoller's map where Inner Languages predomiate is very much the same place which we know from history as the Vedic heartland or Brahmavarta. And the process of Inner Languages clearing out Outer Languages from that central region outward appears to mirror the Sanskritization process that began from the Vedic homeland of the Kurus that has already been documented by scholars such as Witzel. Therefore, Zoller's language map goes totally against the theory of migration of Indo-Aryan languages from outside but supports a inward to outward expansion of Indo-Aryan languages from the Vedic heartland.

2. All the 3 major branches of Indo-Iranian languages as per Zoller's own classification - Outer Indo-Aryan, Inner Indo-Aryan & Iranian, are all found within the Indian subcontinent and quite well spread out across it. Even within the 3, it is not Iranian but Inner Indo-Aryan which appears like the odd one out and which would have likely separated the earliest from the rest of the two since even as per Zoller's own admission a late Proto-Indo-Iranian dialect that got fundamentally influenced by Kartvelian phonology gave way to Outer IA & Iranian. For this to happen, the ancestor of Inner IA must have already got separated from the late Proto-Indo-Iranian dialect that gave rise to Outer IA & Iranian. This Inner Indo-Aryan, the 1st to separate from the rest is however not at the periphery of Indo-Iranian distribution in the subcontinent but right at the centre of it. Even if, instead of 3 branches of Indo-Iranian, we consider the concept of multiple linkage of lects with Iranian and Inner Indo-Aryan linked by multiple Outer IA languages serving as a bridge between the two, as proposed by Zoller, it still ends up highlighting an unparalleled early diversity of Indo-Iranian within the subcontinent This further supports the theory of Proto-Indo-Iranian expansion from within the subcontinent itself and not outside it.

3. Zoller introduces the concept of the linkage of lects to explain the fact that in the northwest of the subcontinent, some 'Iranian' linguistic features are observed in the Indo-Aryan languages while some 'Indo-Aryan' features are observed in typical Iranian languages. As per Zoller, "...the mutual overlaps can be explained by the fact that among the lects of the Indo-Iranian linkage there were a few Iranian and Indo-Aryan lects that have not completely separated from each other." Or as he puts it more eloquently, "...not all dialects completely separated from each other in the post-proto-Indo-Iranian phase. This concerns several archaisms and innovations usually considered as characteristic for either Iranian or Indo-Aryan... I do not mean mutual borrowing, but the fact that in the early phase of the split between Iranian and Indo-Aryan there were also non-Vedic dialects that shared some Iranian innovations with the Iranian side. Conversely, the same is true for a few Iranian languages that have participated in some Indo-Aryan innovations." The very fact that Zoller can glimpse a remnant of the early phase of common Indo-Iranian linguistic unity within the archaic but still spoken Indo-Iranian languages of the northwest of the subcontinent, further supports the argument that Proto-Indo-Iranian could have first diversified within the subcontinent itself for these remnants to still exist in that region.

4. Lastly, Zoller argues for extensive influence of proto-Kartvelian phonological system on both the Outer Indo-Aryan and the Proto-Iranian phonologies in the northern regions of the Indian subcontinent. He also argues that the Karvelian phonological influence was the very reason for the break-up of Indo-Aryan into an Outer and an Inner Indo-Aryan. That both the proto-Iranian and Outer Indo-Aryan branches of Proto-Indo-Iranian were so fundamentally shaped by Kartvelian phonological system within the subcontinent itself at such an early proto stage of their diversification, further strongly argues in favour of the northwest of the Indian subcontinent being the most likely place, by far, for the early expansion, diversification and break-up of Indo-Iranian languages.

Thus, all these points of Zoller taken together cannot but support the contention of Heggarty & Renfrew (2013) that the Indian subcontinent, especially during the rise of its 1st great civilization in its northwestern expanse during the Bronze Age, was the most likely staging ground of the earliest stage of Proto-Indo-Iranian language expansion, break-up and diversification. Even if we were to put aside the question of the homeland of Indo-European languages for the moment, as being in the realms of uncertainty & unknown, we can thus be reasonably certain about the early prehistory of Indo-Iranian languages that make up around 70 % of all Indo-European languages spoken across the world today.

An indication of the greater acceptance of the Indo-Iranian nature of the Harappan linguistic landscape is also reflected in the fact that there are now proposals of Indo-Iranian decipherment of the Harappan script.

Epilogue

We may end this by making observations of some other very crucial parts of Zoller's research that not only further reinforces the idea of a very complex and old history of Indo-Iranian languages in the Indian subcontinent, but it also points to preservation of features among the Indo-Iranian languages of the subcontinent, that do not fit neatly within a Proto-Indo-Iranian framework and may harken to perhaps even older periods of Indo-European unity. We shall make note of 3 of such features highlighted by Zoller.

We may first try to understand what is the basis for the classification of the Indo-Iranian subgroup with Indo-European. What are the unique innovations that define Indo-Iranian as a separate breakaway group from the rest of Indo-European ?

As per Mallory & Adams (Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture),

Indo-Iranian is innovative in four important ways. First, Indo-Iranian are satem languages...Secondly, Indo-Iranian has merged PIE *e, *a, and *o (and *e, *a, and. *o) as a (and ā)...Thirdly, there has been a strong tendency to merge *r and *l...Finally, Indo-Iranian shares with Baltic and Slavic the so-called ruki-rule whereby PIE *s was retracted after *i, *u, *k, and *r.

Zoller's research shows that for atleast 3 of these shared innovations that supposedly define Indo-Iranian, there is evidence of non-conformity in the Outer Indo-Aryan languages.

Rhotacism

Zoller quotes Kobayashi on this,

“Whether Proto-Indo-European *l and *r have merged in Proto-Indo-Iranian is one of the most heavily discussed questions in the reconstruction of Indo-Aryan . . . the paucity of /l/ in the Rgveda may be explained as a characteristic of the Northwestern dialect, which has undergone a development parallel to Iranian, and the distinction between Proto-Indo-European *l and *r is preserved in the Eastern dialects . . . or . . .we assume two dialects for Proto-Indo-Iranian and Indo-Aryan, one with *r and *l and the other with merged *r . . ."

And he also quotes Parpola,

". . . rhotacism . . . [is] the merger of the Proto-Indo-European liquids *l and *r so that PIE *l was systematically replaced with *r . . . Epic/Classical Sanskrit, on the other hand, has in many words preserved the original PIE *l, and there are traces of its preservation in some Iranian dialects as well. . . and in Nuristani . . . These dialects must have separated from Proto-Aryan before it innovated with rhotacism. . ."

Zoller observes that the preservation of Indo-European *l & *r is observed in many Outer Indo-Aryan languages including Nuristani. Thus, rhotacism as a common Indo-Iranian innovation is on weak grounds.

Non-Satemization

Zoller makes notes of the presence of kentum words in Indo-Aryan languages, especially in West Pahari languages like Bangani. He says,

It has long been known that also in Indo-Iranian there are cases of absence of satemization, and below I will add additional evidence from NIA to the list. According to Lipp (2009 i: 11), it is more likely that in the various IE languages in which satem-palatalization occurred, diverging analogical leveling processes took place with the result that in some languages/dialects the palatal variant and in others the velar variant was generalized...

Thus, even satemisation is not universally observed in all Indo-Iranian languages. Therefore, it cannot be a defining feature of Indo-Iranian either.

Non-application of RUKI

Zoller observes (pg 452),

...one finds a considerable number of words where there is not only non-occurrence of RUKI but unmotivated (context-free) variation of s ∼ ś ∼ s. – in several cases accompanied by voice alternations, as shown above wih many examples. Since place-of-articulation variations and voice alternations are characteristic features of Outer Languages...A number of scholars on Nuristani from Morgenstierne to Edel"man, to Buddruss und Degener have argued that in the pre-history of Nuristani the RUKI rule did not apply, wherefore Nuristani had preserved here a unique pre-Proto-Indo-Iranian feature.

Therefore, even the RUKI rule does not unify Indo-Iranian. We may thus understand that the Outer Indo-Aryan languages, and Inner IA too in some cases, appear to be in breach of most of the shared innovations that supposedly define common Indo-Iranian. Such a situation further helps to elucidate the complex and extremely old linguistic situation of the Indo-Iranian languages in the Indian subcontinent with its history in the region perhaps going back to an even earlier stage of Indo-European than the Indo-Iranian period.

Comments

Post a Comment